Andrei Shkuro & the White Wolves

Kuban Cossacks, WW1 partisan tactics, the OG War in Donbas & one man's struggle against Bolshevism.

"A student of the University of Warsaw at the very beginning of the war volunteers for the German front and remains in the ranks for three and a half years, despite repeated wounds and concussions.

Come the hard days of October, there comes a complete disintegration of the army, and Borukaev leaves for his home in far Vladikavkaz, and from there to Nalchik.

At that time, the Bolshevik wave rolls over quiet Nalchik and the Commissar who was sent there, either a barber or an amnestied recidivist, begins his rampage. Requisitioning, collectivization and other usual accessories of the new system flourish.

The Commissar grows more and more insolent, evicts Cossacks who own the best houses, sends armed sailors to bring him other people's daughters and wives, "confiscates" the property of "fleeing counter-revolutionaries," etc. The dissatisfied whisper in the corners, gather in the woods, discuss, complain, and do not know what to do.

This is where the future commander of the “Wolves” comes into play for the first time.

- "You don't know what to do, but I do," he says at one of these secret gatherings.

And that same evening he stalks the Commissar on the way to his quarters, approaches him closely and, without causing unnecessary noise, lets his dagger do the deed.

At dawn he goes into the mountains and without bread, without guns, hiding from the swarming Bolshevik agents, moving only at night, makes his way to Shkuro, who had begun to organize his partisans.

From this moment his private life ends and his days henceforth belong to Russian history."

The newspaper Zhizn (“Life”), Rostov-on-Don, No. 59, July 4th 1919

The experience of guerrilla warfare has been known in the Russian army since the days of Denis Davydov and the War of 1812, but the Imperial Army only mastered it to perfection in the early 20th century. The most famous of Russian Imperial Army’s partisan detachments, which became legendary, were Shkuro's "Wolf Company”. It is worth noting that the first cossacks to use wolf imagery appeared as early as 1900-1901 among the Transbaikal Host. It is believed that the 2nd hundred of the 2nd Argun Regiment invented the characteristic "wolf howl", first started using wolf symbolism and the trademark hats made of wolf fur. The Baikal wolves also participated in battles with the Japanese in 1904-1905. When they suppressed the Boxer Rebellion and crushed the Japanese, the Transbaikal "wolf hundred" was not a partisan unit, but they must be mentioned, since they were the first cossacks to appropriate the wolf as their symbol.

The true story of the well-known "Wolf Company" is inextricably linked to the name of Andrei Shkuro. The future partisan was born in 1886 in Pashkovskaya village (not far from Yekaterinodar). The Kuban Cossack received an excellent military education: the 3rd Moscow Cadet Corps, then a Cossack squadron of the Nikolaev Cavalry School. After school he served in the First Uman Kuban Cossack Regiment. Shkuro began the Great War as a platoon commander in the 3rd Khopyorsky Regiment. The brave cossack participated in heavy fighting in Galicia, where he was repeatedly wounded and for his courage and military talent awarded the Order of St. Anna.

Shkuro received his next award, the Saint George Sword, for the capture of a group of Austrians along with their ammunition and machine guns. In 1915 he was promoted to the rank of yesaul "for excellent service" and during the lull at the front, he proposed to the command a project of a special-purpose detachment. The conditions of positional warfare led to a gradual decrease in the cavalry’s role and many cavalry units were in the rear, clearly underutilized. At this time the idea of creating flying partisan detachments for sabotage and lightning raids behind enemy lines was born. All in all, about fifty such detachments were created (with a wide variety of composition and numbers).

The affairs of the partisan detachments were managed by the Ataman of all Cossack Hosts, Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich. Only a few of these detachments proved really effective, among them the units of Tchernetzov, Annenkov and Shkuro.

Shkuro himself described the structure and tasks of his unit as follows:

Each regiment of the division sends from its ranks 30-40 of the bravest and most experienced cossacks, who are then organized into a partisan squadron. It penetrates into the rear of the enemy, destroys railroad lines, cuts telegraph and telephone wires, blows up bridges, burns warehouses and generally, as best it can, destroys communications and supplies of the enemy, incites the local population against them, supplies them with weapons and teaches them the technique of guerrilla action, and keeps them in touch with our command.

His superiors approved Shkuro's project, and he was summoned to Boris Vladimirovich in Mogilev. Drills for partisans and experiments with new tactics and weapons were happening there. At one of these experiments, when incendiary bullets were being tested, the Tsar himself was present. He gladly joined in the exercises and took a shot at a wooden wall, which promptly caught on fire. These special bullets were to be used during sabotage activities in the German-Austrian rear, but the invention never made it to the troops until the end of the war.

In late 1915 Shkuro formed the "Kuban cavalry unit for special assignments". The first task of Shkuro's special forces was a raid on the German rear, during which the cossacks destroyed a whole company of Germans behind enemy lines and captured several dozen enemy soldiers, while losing only two men. These raids continued, and every two days the guerrillas penetrated behind enemy lines, exhausting enemy manpower and obtaining information. Soon the Kuban cossacks’ first major operation awaited - the capture of the headquarters of a German division. Local residents cut the telephone lines, and the unit quickly reached the headquarters by horseback (about 60 kilometers), where it overpowered the guard company and captured the entire division headquarters along with the division commander. The Germans managed to move units to rescue their headquarters, and a hard fight ensued. The captured general tried to escape and was cut down. For three days the partisans hid from the huge pursuing German forces and still reached their own, bringing with them important documents from the headquarters and several captured officers. For this glorious deed Shkuro was presented with the St. George Cross.

When the activities of the partisan unit became more complicated, Shkuro asked to join the Southwestern Front, where cavalry battles were still taking place. Since he proved to be a brave and talented partisan, Shkuro was given several more detachments, in particular Bykadorov’s Don Cossacks, Abramov’s Ural Cossacks and the Partisan detachment of the 13th Cavalry Division. Shkuro's unit grew to 600 men and operated in the southern Carpathians, supporting the Russian infantry offensive. While the infantry attacked the enemy, Shkuro penetrated the frontlines and disrupted communications, smashed supply lines and headquarters, and sometimes attacked the enemy from the rear, creating a monstrous pincer, which the enemy could rarely withstand. In the battle of Karlibaba Shkuro was seriously wounded, and soon after his unit was attached to the 3rd Cavalry Corps, headed by the legendary Count Keller, nicknamed "the first saber of the Russian cavalry".

Shkuro served under Keller until the Revolution and the Count's forced resignation. The Provisional Government’s Order No. 1, which became a nail in the coffin of the Russian army, led to the degradation of the infantry, which often clashed with the cossacks, who, according to Shkuro, had a critical attitude toward the revolutionaries. When it almost came to gunfights with the "soldiers' committees," Shkuro decided to leave the front and return to the Kuban. On his way back he described the following incident:

On April 18, 1917. On April 18, 1917 (May 1, New Style) we drove up to Khartsizsk. Already from afar we could see a huge crowd of 15,000 rallying. Countless red, black, blue (Jewish) and yellow (Ukrainian) flags were flying over it. Barely had our train stopped when the workers’ delegations appeared to inquire who these people were, and why they were without red flags and revolutionary emblems.

- We are going home, answered the cossacks, we do not need that stuff.

Then the "conscious" workers began to demand the surrender of the command staff, being counter-revolutionaries, to the court of the proletariat. Wachmeister Nazarenko of the 1st company jumped up on the machine-gun platform.

- You say, he shouted, addressing the crowd, that you are fighting for freedom! What kind of freedom is that? We don't want to wear your red rags, and you want to force us to. We understand freedom differently. The cossacks have been free for a long time.

- Beat him, smash him! - the crowd roared and rushed towards the train.

- Hey, cossacks, to the machine guns! - Nazarenko commanded.

In a moment the machine gunners were in position, but there was no need to shoot. The crowd scattered, crushing and knocking each other over, filling the air with screams of animal horror, and only the moans of the bruised people crawling on the platform and the motley "embodiments of freedom" lying around in abundance testified to the recent "spontaneous rise in the feelings of the conscious proletariat".

After a vacation in his home region, Shkuro took his unit General Baratov in Persia. After spending some time there, he decided to return to Russia and wandered the Caucasus and Kuban for some time. He had been witness to all the pleasures of the Revolution, from being arrested by sailors to the attempt to force him into Bolshevik service, and at last he decided to take the path of resistance. Shkuro learned that Denikin was assembling an army somewhere... After long communication with the cossacks, he realized that they were strongly displeased by the Bolsheviks, and began to form the "Southern Kuban Army" - the first White Guards' movement of the Kuban.

The "Wolves" at this time were commanded by Borukaev (who was mentioned in the quote at the beginning of this post). The gathering at the "Wolf's Glade", the campaign to Stavropol, the winter battles with the Bolsheviks - Borukaev was a brave warrior and a true Russian patriot. After reuniting with the Volunteer Army, Shkuro reported to the command that he did not want to command the Stavropol garrison, as he was "not made for defensive fighting”. The White Stavka agreed to Shkuro’s proposal to go to Batalpashinsk to prepare another uprising. From that moment he had already become the chief of the "Separate Kuban Partisan Brigade".

At the head of this brigade Shkuro moved to Kislovodsk, which he took in September 1918. Soon he had to retreat from the city under pressure from the huge Bolshevik forces. When the 1st Caucasian Cossack Division was sent to destroy the Reds in the Batalpashinsk department, Shkuro took his "Wolf Company", overtook the division and led them himself into an attack on the Bolsheviks' vanguard, which was completely defeated. Soon the "Wolf Company" grew to a "Wolf Division" and served as Shkuro's personal convoy and personal reserve. This is how Colonel Yeliseyev described the "Wolves”:

There stood the 'Wolf Division,' General Shkuro's personal convoy. I saw them for the first time, which is why I was interested. In addition, I heard from my officers criticism, which turned out to be completely unfounded, that the "Wolves" were stationed in the center of the cities as a privileged part of Shkuro's entourage. But they added that when it was necessary or in case of a battle failure, Shkuro threw them into the thick of the fighting, and they never retreated... That is why I was interested in getting to know them.

All the "Wolves" wore shaggy, wolfskin hats. All were well dressed, almost all in Circassian coats. Many had silver daggers. Their horses were healthy.

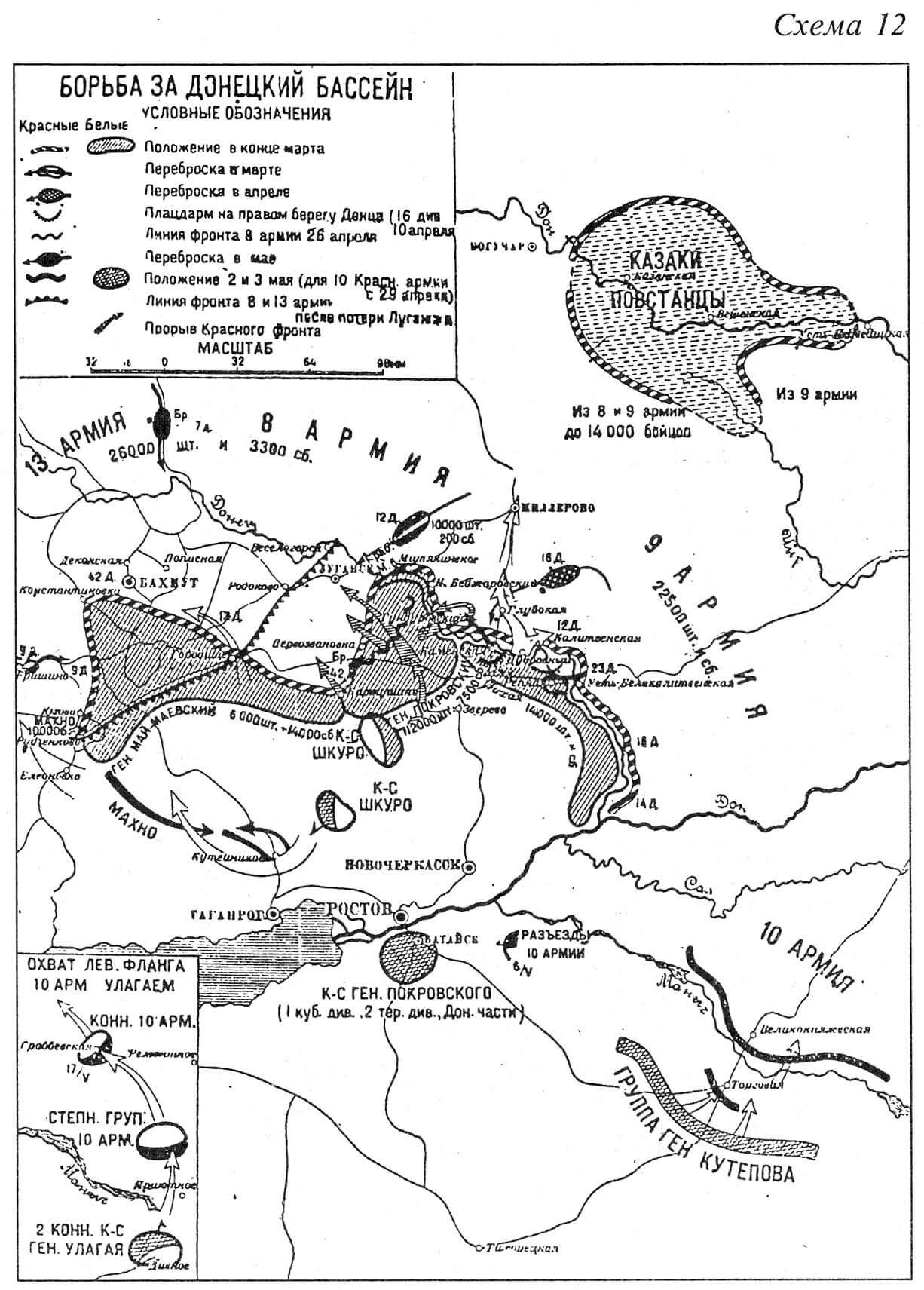

In the eventful Civil War there were bitter, desperate episodes, but there were also periods of triumph. Such a time fell between the Second Kuban Campaign and the Moscow Directive. Thus, by the end of the spring of 1919, the general situation looked good. The Whites were advancing on all fronts, repulsing the Reds both in the Donbas and in the Caucasus; Tsaritsyn was encircled; the army was preparing to march on Moscow. To this end it was divided - on the Western section of the front, units of the Armed Forces of Southern Russia were preparing to clear the Donbas of Communists in order to preserve the left flank of the offensive against Moscow.

The Volunteer Corps was making its way deeper into Ukraine. Here, the situation looked promising: against 50,000 soldiers of the Armed Forces of South Russia, there were only 100,000 Reds, which, in terms of the Civil War, didn’t mean a numerical advantage for the Communists at all. The Volunteer Army pounced on the Reds, capturing Slavyansk by the end of May and sending the 8th and 13th Soviet armies fleeing over the Seversky Donets River. These armies were in such a deplorable condition that Trotsky effectively recognized their destruction by ordering the formation of new defense centers in Kharkov and Yekaterinoslav (now known as Dniepropetrovsk, or “Dniepr”.). Fresh reinforcements were sent there, consisting of elite (as much as that was possible) Red Army soldiers, Communist sailors, and Red cadets. The defense of these towns was prepared feverishly, right down to arming the local "proletariat”.

At the same time Voroshilov was made commander of the 14th Red Army, which was given the task of saving the 8th Army from the White Guard offensive. Voroshilov, who had no military education, suffered a crushing setback.

Trotsky’s and Voroshilov's failure had a name: Andrei Grigorievich Shkuro.

The 14th Army rushed to Yuzovka and Slavyansk in a desperate dash, but Shkuro's cavalry crushed them utterly, just like Makhno's cavalry group, of which only bloody scraps remained. After hanging a number of communists and anarchists (and sending the regular mobilized peasants home), Shkuro moved on in the direction of Yekaterinoslav, to finish off a frightened Voroshilov. After these battles the commander of the Volunteer Army, Yuzefovich, promoted Shkuro to the rank of lieutenant-general; at the same time he was approved as commander of the cavalry corps, consisting of his own Wolves and the 1st Terek Cossack Division.

Makhno's attacks continued to do sensitive damage to the White advance, and Shkuro was given orders to burn down the bandits' lair. Leaving the Terek Division to support the Volunteer Corps, advancing on Kharkov, he moved with the remnants of his corps on Guliaipole, the capital of the Makhnovists and where they stashed their loot. In the course of heavy fighting, the anarchists were defeated and scattered, leaving the local infrastructure and the warehouse at the mercy of Shkuro. Before moving on, Shkuro burned the Sinelnikovsky railroad junction.

Meanwhile, May-Mayevsky had liberated Kharkov and moved his headquarters there; General Denikin had also arrived there, and Shkuro had also been summoned. Kharkov greeted General Shkuro with joy: the city had heard much about his successful operations against the Reds and Makhnovists, and they arranged a solemn meeting, including a series of sumptuous banquets, during which he was presented with icons and various gifts. While Shkuro was in Kharkov, his Caucasus Division was fighting on the left bank of the Dnieper River, toward Yekaterinoslav.

The division was commanded by its former chief of staff, Shifner-Markevich. He sent three hundred partisans to the other side of the Dnieper for sabotage, reconnaissance, and raids on the Red rear. On July 15 in the course of such a raid they managed to get to the other bank, cut off the Red sentries and seize two artillery batteries. The guns were hurriedly turned around and opened fire on the Red infantry, which panicked and fled, dropping their weapons. However, the Red artillerymen fired on the bridge over which the partisans passed - they were cut off from the main forces of the division. This raid presented a dilemma for Shifner: on the one hand, he had clear orders to stay on the left bank of the Dnieper, on the other hand three hundred partisans surrounded by hordes of Bolsheviks...

Shifner quickly coordinated the operation with Shkuro and threw the entire division to save the brave vanguard, crossing the Dnieper and moving toward Yekaterinoslav. The Red sailors and the "revolutionary" proletariat could not resist the onslaught of the White troops; despite the convulsively organized (by Trotsky personally!) defense of the city, Yekaterinoslav was quickly taken, and the 13th Army collapsed and melted away. According to Denikin's testimony, "The defeat of the enemy on this front was complete," and according to the chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, the 13th Red Army "shamefully disintegrated."

Shkuro's corps found itself in a difficult situation. Victory in Yekaterinoslav was easy, but the occupation of the city was not in the plans of the command; the assault was a direct violation of the general directive. Local residents, having experienced the horrors of Bolshevism, fell on their knees before Shkuro and begged him not to leave the city - they feared the return of the Reds. Unable to refuse the townspeople, the White units remained in the city. Shkuro's soldiers entering the town were greeted with bread and salt, tears, icons, and flowers. As elsewhere, White units were perceived as liberators from Red barbarism, Red violence, and Red terror.

The city's clergy served prayers in honor of the White heroes, workers volunteered to work for the Volunteer Army as much as they could, fixing armored trains and repairing cannons and firearms. Starving after the Red occupation, the city needed bread, and Shkuro brought several trains of flour intended for his corps; he distributed them free of charge to the food stalls of Yekaterinoslav, saving the lives of many people. Grateful residents prayed daily for Shkuro and his soldiers, and a large number of residents joined the ranks of the Armed Forces of South Russia.

However, the situation remained tense; the city was still in danger. The vastly superior Communist forces under the command of Dybenko repeatedly launched counteroffensives and did everything they could to recapture the city. Despite their best efforts, the Reds failed to overwhelm Shkuro. Together with Shifner-Markevich, he defended Yekaterinoslav with all his strength, all available tactics. The Cossacks maneuvered with exquisite skill, circling a hundred kilometers around the city and perfected their strategy of many lightning-fast, pinpoint strikes all over the place, breaking Dybenko's army first into small pieces and then smashing them into a non-functional jelly. With the retreat of the last Communist detachments, Yekaterinoslav was saved.

Having liberated the city from the Bolsheviks & saved the citizens from starvation, Shkuro left Yekaterinoslav with his corps in the direction of Kharkov, from where he moved on. Yekaterinoslav forever remembered its savior, who provided the city with a brief respite and relative happiness in the mad flames of the Civil War. But he was also remembered by the Reds: the general's name terrified them, and at the sight of the banners of the Wolf Hundred, even the most steadfast Red Army soldiers fled in panic.

The successes of the White Movement continued: Shkuro stopped the Bolshevik counterattack on Kharkov, defeating several infantry divisions of the enemy and capturing 7,000 Red Army soldiers; at the same time the famous Mamontov Raid was taking place, sowing panic and devastation in the Red rear further North. The White troops were getting closer and closer to Moscow; soon Kursk and Orel also fell into their hands.

After successfully defending the Donbas against the Bolsheviks and defeating the Makhnovists, Shkuro was sent to other parts of the front. He proposed to Denikin, with whom he was on very difficult terms, to start a large-scale guerrilla movement in the Red rear, but the Commander-in-Chief refused. The leader of the Wolves came up with a plan to support the Moscow directive: to create a multitude of mounted sabotage detachments which were to blow up railroad tracks, burn bridges, cut off telegraph lines and eliminate the Bolshevik headquarters. Denikin probably did not want any Cossacks, much less partisans, to make a huge contribution to the liberation of Moscow if it meant less glory for him personally. Denikin never even seriously considered Shkuro's plans, and the Moscow directive failed (and with it, perhaps, the entire Civil War).

However, Shkuro's experience and ideas did not dissolve into history. Other people took advantage of his ideas... In particular, the Soviet army leadership. Before Operation Bagration began, exactly what Shkuro proposed to do to the Soviets was done to the Germans. The paralysis of Heeresgruppe Mitte served as ideal ground for the Soviet offensive. If Denikin had listened to Shkuro in his time, there might not have been an Operation Bagration - or even a World War 2 at all.

In the fall of 1919, Shkuro takes Voronezh, but by that time the White advance on Moscow had already failed. As Shkuro had predicted, the Bolsheviks moved a huge force by railroad and stopped the Armed Forces of South Russia. By the end of the year the Whites were forced to retreat to Novorossiysk, from which they evacuated to the Crimea. In the Crimea, Pyotr Wrangel became the new Commander-in-Chief of all White forces. He had an even lower opinion of Shkuro, though. During another personal conflict, Wrangel dismissed Andrei Grigorievich from the Russian Army, who emigrated to France.

While in exile, Shkuro earned a living by teaching movie stuntmen on horseback. He advocated a further struggle against the Bolsheviks and in 1941 proposed to the German leadership the creation of Cossack units within the Wehrmacht. These units eventually included several "Wolf Squadrons," but none of them had anything to do with Shkuro. He dealt with the affairs of the Cossack Reserve under the General Directorate of Cossack Troops. His "Wolves" never returned: many times he offered the Germans to create a Wolf Company for sabotage activities in the rear of the Red Army, but he was refused. We can assume that the Germans feared a spontaneous Cossack uprising led by Shkuro, which would have served Russian rather than German needs.

In 1945, Shkuro and Krasnov (the leader of the Don Cossacks who served under German flags) broke through to Austria, to the notorious town of Lienz, where a large number of Cossacks and their families were located. The British extradited the Cossacks to Stalin, along with ataman Krasnov and General Shkuro. At the time of his arrest, the Chekists reproached him that he had "epaulettes made with the same lining as the Nazi generals," to which Shkuro laconically replied that "he couldn’t find any other". The Kuban Cossack quickly established good relations with the Red Army men and amused them with anecdotes and stories about the Civil War. Nevertheless, he realized the hopelessness of the situation and several times tried to commit suicide on the way to Moscow. After a month of interrogations by the NKVD he was sent to the infamous Lubyanka prison. Interrogations by SMERSH were followed by torture and further interrogations at the NKVD headquarters... Shkuro, as well as Krasnov, refused to repent.

The Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced both to death for treason to a country they were never citizens of.

On January 16, 1947 the death sentence was executed.

Not our finest hour.